If you love old technology, the Information Technology History Exhibition at the Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra in Szeged may feel like the right place for you. This space is clearly aimed at real tech enthusiasts rather than casual visitors looking for a polished, interactive experience. You’ll move from room-sized computers to early Macs from the 1990s, walking past old telephones and mechanical calculators along the way. Many of these machines once filled offices and laboratories, and the overall atmosphere feels closer to a technical archive than to a modern museum exhibition.

Table of Contents

About the Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra in Szeged

The Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra in Szeged is not a museum but a multi-purpose cultural and educational centre serving the city. Inside, you’ll find an information desk focused on local events and activities. It’s a useful stopping point for visitors trying to understand what is happening in town.

PLAN YOUR TRIP TO HUNGARY

For a road trip in Hungary, choose a Holafly eSIM: you will have unlimited internet to use Google Maps or any other GPS app, and you can share photos and videos in real time on WhatsApp and social media without any worries.

To travel with complete peace of mind, don’t forget to also take out Heymondo travel insurance, which protects you from unexpected events and ensures a worry-free holiday.

The building also includes laboratories used for workshops and educational programmes, mainly aimed at students. There is a dedicated children’s area, accessible with a separate ticket, which works more like an indoor activity space. Part of the Agóra is also home to the American Spaces network in Hungary. It hosts talks, cultural events and educational initiatives connected to the United States.

Within this broader setting, the Information Technology History Exhibition is just one part of a much larger complex rather than its main attraction.

What to See in the Information Technology History Exhibition

The Information Technology History Exhibition is a wide collection of old computers that shows how technology developed over time, especially in Hungary and Eastern Europe. You’ll move from mechanical calculators to early personal computers, and from experimental machines to domestic technology.

Not everything is easy to follow if you don’t speak Hungarian, but the collection itself is surprisingly rich. The following sections will guide you through the most interesting parts of the visit, from historical figures and early inventions to retro consoles and robot prototypes that anticipated modern domestic robots.

Hungary’s Role in the History of Information Technology

At the Information Technology History Exhibition, some panels introduce you to key figures in Hungarian technological history through portraits, technical drawings and short biographies. The aim is to show that Hungary has not only used technology, but has also produced ideas, devices and research that have shaped the wider story of computing.

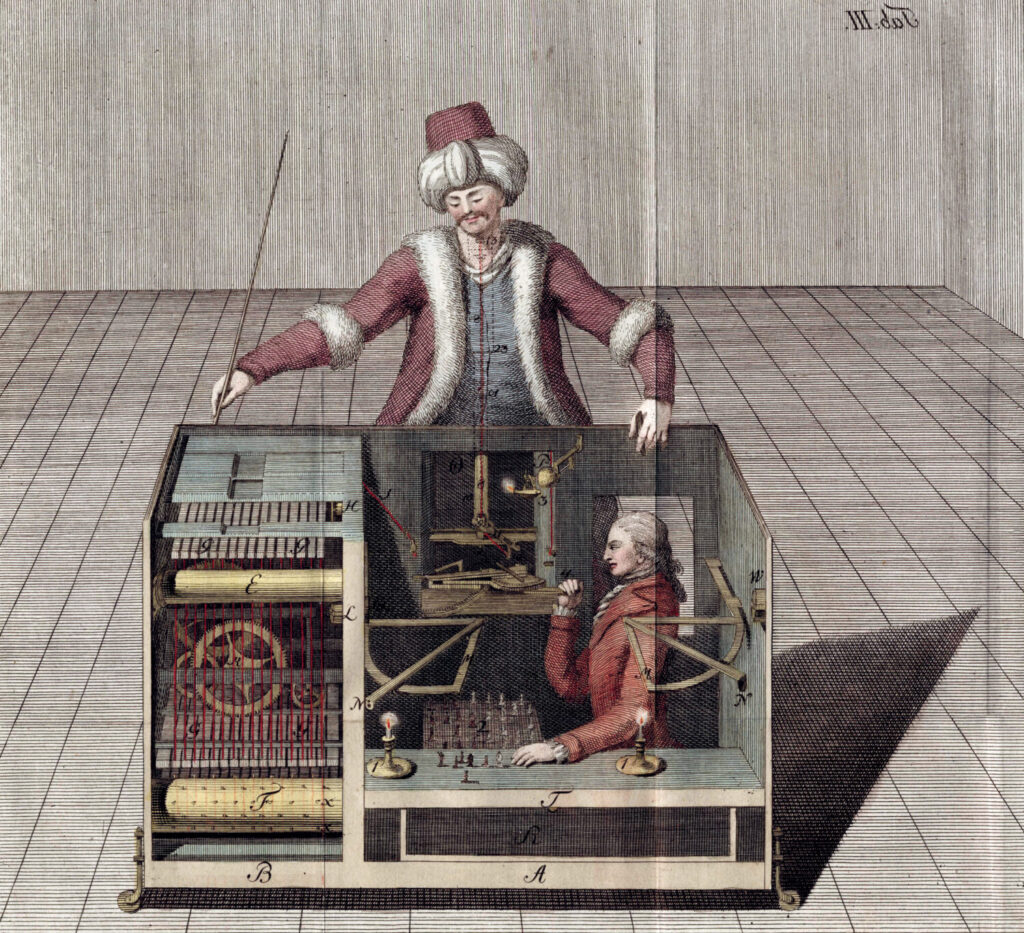

Farkas Kempelen and The Turk

Hungarian computing history goes much further back than you might expect. One of the earliest figures is Farkas Kempelen. He became famous across Europe in the eighteenth century for his chess-playing automaton known as The Turk. Audiences believed it could defeat even the best players of the time. In reality, the pieces were controlled by a chess master hidden inside the machine, using levers and magnets. The machine toured and was exhibited for 84 years as an automaton and continued giving occasional exhibitions until 1854, competing with the most famous personalities of the time, when it was eventually destroyed in a fire.

Ányos Jedlik and Early Technological Innovation

Another pioneer is Ányos Jedlik, a monk, physicist and inventor. He built early electric motors and experimented with electromagnetic rotation long before it became mainstream. In Hungary, he is also remembered for inventing artificial soda water, which later became the basis for the mass production of fizzy drinks. Hungarian secondary school students know Jedlik because he created a new type of mineral water known as artificial soda water. Thanks to him, an industry based on the mass production of carbonated non-alcoholic beverages was established, and soda water also became a recognised mineral beverage.

From Engineering to Computer Science

Moving into the twentieth century, István Juhász worked on precision instruments and engineering design, helping to modernise Hungarian industry. In theoretical computer science, Rózsa Péter laid the foundations of recursive function theory, publishing influential works that shaped programming logic worldwide. Finally, Klára Dán von Neumann became one of the world’s first programmers. She worked on ENIAC and early stored-program computers in the United States, quietly shaping modern computing from behind the scenes.

Mechanical Calculators and Pre-Digital Computing

Mechanical calculators were essential tools in offices and industry during the first half of the twentieth century. They represent the final stage of calculation before the transition to electronic computing. They carried out complex mathematical operations entirely through mechanical movement, without electricity or digital technology.

In socialist countries, their development followed a different path from that of Western Europe and the United States, often relying on independent engineering solutions and local production. In the 1950s and 1960s, several Eastern European countries produced their own mechanical calculators. These machines were mainly used in administration, industry and education, at a time when electronic computers were not yet widely available.

At the Information Technology History Exhibition you can learn how machines developed in the Soviet Union were typically large, robust and intended for heavy daily use. They were produced in large numbers and distributed across government offices and factories. East German models focused on durability and long-term operation in institutional settings.

Several Polish manufacturers produced mechanical calculators for both domestic use and export within the Eastern Bloc. Czechoslovak machines were known for their solid mechanical construction and precision engineering. Hungary also developed and manufactured mechanical calculating machines. Some models were produced locally, while others were adapted from foreign designs under licensing agreements.

From Room-Sized Computers to Early iMacs

In the Information Technology History Exhibition, you’ll see both Hungarian transistor computers and machines from other countries. The earliest computers were huge, often as big as a wardrobe, and worked thanks to transistors. The transistor, usually made from silicon, functions as an electronic switch and allows computers to use simple on-off signals, known as binary code.

In 1958, Jack Kilby built the first integrated circuit, placing many transistors on a single silicon chip. This marked the beginning of the microelectronics revolution. Computers became smaller, faster and more affordable, eventually moving into homes and offices. In 1971, the Intel 4004 introduced the microprocessor, placing the entire central unit on one chip and changing computing forever.

From Past to Future Through Computing Prototypes

A section of the Information Technology History Exhibition is dedicated to a giant robotic ladybird. The model demonstrates different types of reflex behaviour rather than following pre-programmed instructions. It responds to light, sound and physical contact, showing how machines can react to the environment without human control, in a similar way to modern robot vacuum cleaners, like Roomba.

The first experimental version of this robotic ladybird was built in 1956–57 at the University of Szeged, commissioned by the Mathematical Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. This device is an early and fascinating example of automated behaviour, long before domestic robots became part of everyday life.

The Retro Room with Computers And Consoles from the 1980s and 1990s

At the end of the exhibition, you’ll reach a room dedicated to computers and game consoles from the 1980s and 1990s. This is the part that feels closest to a classic retro collection and could easily become the most engaging area of the visit.

I’d love to try one of the early iMacs, but during our visit almost everything was switched off. The machines were there to look at, but we were only able to try two consoles with Super Mario and Mario Kart.

Curiously, my son, born into a fully digital world, didn’t manage to use the old Mario Kart console at all. Without a modern controller, the system felt completely unfamiliar to him. What was once cutting-edge technology suddenly became confusing and difficult, showing just how fast gaming and design have changed in just a few decades!

Practical information for planning your visit

The Information Technology History Exhibition is located inside the Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra in Szeged. The Agóra itself sits in the city centre, which makes it easy to visit on foot if you’re staying nearby. If you’re based in a more peripheral area, you can use the local buses or trams. You can check routes and timetables easily on Google Maps.

Each attraction inside the Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra, including the children’s area, requires a separate ticket. I recommend stopping at the information desk near the entrance to check what’s included in each section. If you don’t speak Hungarian, it’s easy to feel a little lost. Most signs and general information are only available in the local language.

Inside the Information Technology History Exhibition itself, most of the captions are in Hungarian only. Just the first two panels at the very beginning of the exhibition have been translated into English. Unfortunately, there’s no English-speaking staff available inside the exhibition. Much of the technical and historical context is lost if you don’t understand the language. If you’re lucky enough to visit with someone who speaks Hungarian, the experience is likely to be far richer. The collection, in fact, is impressive and quite unique.

Informatika Történeti Kiállítás

Information Technology History Exhibition

Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra

Kálvária sugárút 23, 6722 Szeged, Hungary

Where to Stay in Szeged

When visiting Szeged, staying in the city centre makes everything easier. All the main sights are within walking distance, including the Cathedral, the New Synagogue and the National Theatre.

For a comfortable hotel stay, Art Hotel Szeged offers modern design in the heart of the city. The restaurant serves Hungarian and international dishes, breakfast is included and the River Tisza is just a two-minute walk away.

If you prefer an apartment, the Noir Hotel residence provides air-conditioned studios with a kitchenette, coffee machine, fridge and private bathroom. A continental breakfast is available on site. For a budget-friendly option, Frasolis Studio Apartman is a small, but well designed apartment, ideal for two people. It’s simple, cosy and offers excellent value for money.

Final Thoughts on the Information Technology History Exhibition

By the time you leave the Information Technology History Exhibition, you’ll probably have mixed feelings. You’ll see an impressive number of rare machines, but you’ll also feel the limits of an exhibition that isn’t designed for international visitors. Even so, this is still a meaningful stop if you enjoy unusual museums and want to explore a lesser-known side of computing history in Hungary.

If you’re planning a day focused on science and learning in Szeged, it pairs well with another unexpected place: the Interactive Science Knowledgestore. While the IT exhibition focuses on machines and technology, the Knowledgestore shows you how natural science was once taught through real classrooms, specimens and physical objects.

Together, the two museums offer a broader picture of how knowledge evolved in university environments, from early computers to old anatomy rooms. And they are only a small part of what Szeged has to offer, from elegant Art Deco buildings to wide green parks along the river. Share your impressions in the comments and help other travellers decide if the Information Technology History Exhibition belongs on their itinerary.